In this Autumn/Winter edition of The Expert Series, RAC member Kristof Dhont (University of Kent) & colleague, Maria Ioannidou (University of Bradford) examine the motivations behind going vegan.

What motivates people to go vegan?

From a quick look at the websites of some of the major vegan and animal advocacy organisations (e.g., Why go vegan?), we immediately learn about the four main reasons for becoming vegan: for the animals, for your health, for the environment, and for other people (i.e., human rights and social justice concerns). Psychological research has shown that the first three also represent the key motives that omnivores as well as vegetarians and vegans generally mention when asked about possible reasons to eat less or no meat and more plant-based products.1-5

However, although it is interesting to learn about meat reduction motives as well as about the perceived benefits of plant-based food, it does not provide a clear answer as to why people actually go vegan. Indeed, much of the narrative regarding why people go vegan (or at least adopt a vegan diet) seems to be informed by studies that were conducted with samples of omnivores or meat reducers, or samples that grouped vegetarians and vegans together. This is not entirely surprising given that the dominant research focus in this area has been on meat consumption and why people reduce or stop eating meat. Psychological research that includes large samples of vegans or that investigates why some people decide to quit the consumption of all animal products and not just meat is still scarce. Yet such research is necessary to understand people’s motives for going vegan.

So, why do people go vegan? Ideally, researchers would investigate people’s attitudes and motivations at the time they go vegan. Then, the researchers could follow this group of vegans over a fairly long time period to track their attitudes and their adherence to key aspects of a vegan diet and lifestyle. Unfortunately, such research is currently not available. An alternative yet smaller-scale approach is to identify some of the key differences in motivations and underlying attitudes between vegans and other groups such as omnivores and vegetarians. Using such comparative approach, a number of studies have already identified pronounced differences between meat eaters and meat abstainers as well as between subgroups of vegetarians. We will first have a look at the findings of these studies.

Motivations of Meat Eaters versus Meat Abstainers

A key difference between omnivores and vegetarians concerns the different moral and ideological values they endorse. Findings of several studies collectively show that, on average, omnivores have a stronger preference for social hierarchy and group-based dominance in society, whereas vegetarians tend to place a higher value on social equality. Omnivores also tend to value cultural traditions more strongly, adhere more closely to social norms, and exhibit higher respect for authority. Thus, omnivores often endorse values associated with right-wing ideology. In contrast, vegetarians are more likely to embrace social change, liberal values, and left-wing ideology.5-8

Given these marked differences between omnivores and vegetarians, it will come as no surprise that these general ideological beliefs about how societies should be organised are also implicated in the way people perceive and treat non-human animals. Indeed, research shows that conservatism and right-wing beliefs regarding social dominance and authoritarianism are associated with lower concern about animal welfare and rights, greater acceptance of animal exploitation, and stronger beliefs in human superiority over animals and nature. People who endorse right-wing ideologies also tend to eat more meat, hold more negative attitudes towards vegetarians, and perceive vegetarianism and veganism as threats to cultural traditions related to animal consumption at higher rates. In contrast, people who value social equality and compassion and are morally opposed to group-based dominance tend to hold views that reject oppressive systems and practices, including animal exploitation.9-16

To be clear, despite these ideological differences between meat eaters and meat abstainers, the majority of left-wing adherents still eat meat and other animal-based products. Without a doubt, just like those on the right, those on the left still often eat animals despite being more inclined to support animal rights, to eat less meat, and to hold more positive attitudes towards vegetarianism and veganism. One explanation for this ostensible disconnect between values and behavior is that people engage in psychological strategies that make eating and exploiting animals feel morally acceptable. This enables them to profess to be animal-lovers while also eating animal-based products. Interested readers can read about these psychological strategies in this previous article.

Clearly, as in several other life domains, ethical and ideological values are closely entwined and appear to lay at the heart of the psychological differences between meat eaters and meat abstainers. These values thus shape the ethical motivations to refrain from eating animals. And while most vegetarians recognise the health and environmental benefits of plant-based food systems, several studies indicate that a majority of vegetarians report ethical concerns about the treatment and killing of animals as the primary motivation for quitting meat consumption, rather than health or environmental reasons. Furthermore, some evidence suggests that the sizable minority of vegetarians who do self-identify as health or environmental vegetarians may be less successful in sticking to vegetarianism than animal ethics vegetarians. In other words, when considering consumption behavior, some self-identified health and environmental vegetarians tend to follow a low-meat (or ‘flexitarian’) rather than a vegetarian diet. Similarly, health concerns tend to be more central among those who try to reduce but are not willing to quit their meat consumption, also referred to as ‘meat reducers’. With respect to animal welfare concerns (or lack thereof), meat reducers resemble omnivores more than that they resemble vegetarians.5, 17-19

Taken together, animal ethics emerge as the key motivation to be vegetarian and provide a clear and consistent value system that rejects harming non-human animals. But if this is the case, why are vegetarians not turning vegan? The ethical problems associated with the dairy and egg industry are well documented and arguably exceed the levels of animal suffering associated with the meat industry.

If (ethical) vegetarians are indeed opposed to animal exploitation, why do they still consume dairy products and thus contribute to an industry where cows are treated like commodities from the day they are born and are forcibly impregnated every year? Moreover, cows in the dairy industry are killed when their milk production declines, and calves are torn away from their mothers often within the first hours of birth so the mother’s milk can be used for human consumption.

If (ethical) vegetarians are indeed concerned about the welfare and interests of non-human animals, why do they still consume egg products and thus contribute to an industry where hens are forced to live in confined, overcrowded conditions that prevent them from exhibiting any natural behaviors? Moreover, male chicks in the egg industry are considered trash and suffocated to death or thrown into an industrial macerator while being alive.

For those who do not consider the gustatory pleasure of eating bacon a valid moral justification for exploiting and killing animals, how much sense does it make to consider the gustatory pleasure of eating cheese a valid moral justification for exploiting and killing animals?

Motivations of Vegetarians versus Vegans

In order to better understand what distinguishes the motives of vegans from those of vegetarians, we will now look more closely at the psychological differences between both groups. The few studies that have compared attitudes and values of vegetarians revealed a fairly straightforward picture. Compared to omnivores, both vegetarians and vegans hold more positive attitudes towards animals and show greater concern for animals. However, these attitudes and moral values tend to be stronger among vegans compared to vegetarians. Vegans also exhibit an even stronger opposition to group-based inequality and social dominance, and they recognize greater similarities between humans and non-human animals in terms of their emotional experiences and mental capacities.16, 20-23 The findings of these studies thus tentatively suggest that vegetarians and vegans hold similar moral motivations to abstain from meat consumption, yet vegans apply these values more broadly and consistently across their consumption behavior and lifestyle, moving beyond merely meat consumption.

To obtain clearer evidence for these ideas, we conducted a new study and surveyed a large group of vegans and vegetarians, recruited through social media channels.24 We report some of the initial key findings here. To allow for a clear comparison between vegetarians and vegans, we only used the responses of self-identified vegetarians who reported that they did not consume any type of meat or fish in the past three months, as well as the responses of self-identified vegans who reported that they did not consume any type of animal-based food in the past three months. This resulted in a group of 182 vegetarians and a group of 335 vegans for our analyses. As can be seen in the table below, both groups were very similar in terms of average age and representation from different gender identity groups.

Table 1.

|

|

Vegetarians (n = 182) |

Vegans (n = 335) |

|

Gender identity |

65% women 30% men 3% non-binary / agender / gender fluid 2% prefer to self-describe / not to say |

66% women 29% men 3% non-binary / agender / gender fluid 2% prefer to self-describe / not to say |

|

Average age |

34.82 (SD = 10.73) |

36.96 (SD = 12.37) |

|

Primary reason |

65.7% Animal ethics 23.7% Pro-environment 10.5% Health |

88.9% Animal ethics 8.4% Pro-environment 2.7% Health |

As part of the survey, we presented participants with a list of possible motives why people do not eat meat and asked them to rate the importance of each of the reasons for them not to eat meat. The list included statements related to health motives, environmental motives, and animal rights motives, and were based on the Vegetarian Eating Motives Inventory developed by Chris Hopwood and his colleagues.2 We also presented participants with a very similar list of possible reasons why people consume less or no dairy and egg products and more plant-based products, and again asked them to rate the importance of each of the reasons. Interested readers can find the list of statements in Table 2. Comparing the responses of the group vegetarians with those of the group vegans revealed several interesting insights.

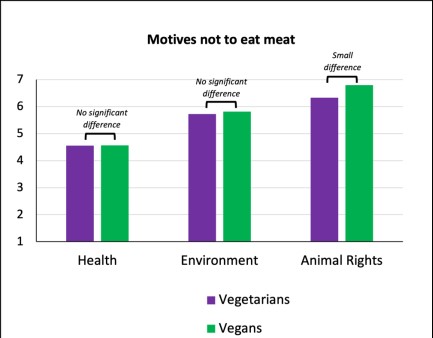

As can be seen in Figure 1, the two groups did not differ much from each other with respect to their motives not to eat meat: for both groups, health was the least important motive, followed by environmental benefits, whereas animal ethics were the most important motive for both groups. In fact, animal ethics were considered only slightly more important by vegans as a motive not to eat meat.

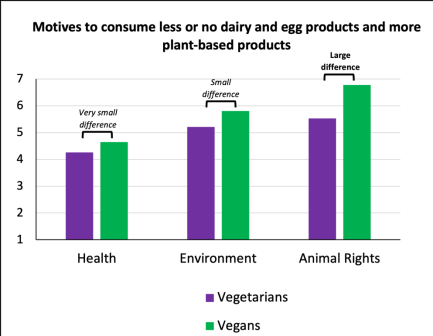

However, more pronounced differences emerged when looking at the motives of vegetarians and vegans to ditch dairy and eggs and to eat vegan. Again, both groups considered health the least important motive, whereas animal ethics were considered the most important motive. More importantly, although vegetarians considered all three motives less important than vegans, the most striking difference between the two groups was that vegetarians considered animal ethics clearly less important when it came to dairy and eggs. In other words, whereas opposition to animal suffering and support for animal rights were of great importance in shaping vegetarians’ motives not to eat meat, vegetarians seemed to care less about these reasons when considering dairy and egg products. In contrast, vegans considered animal ethics consistently very important. Moreover, the vast majority (almost 90%) of the vegans in our study indicated animal ethics as the primary reason for their diet.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Next, we wondered whether vegetarians and vegans also differ from each other in the extent to which they feel moral concern for different types of animals. Previous studies conducted in the US and UK demonstrated that people’s judgments about the need to care about animals depends on the social-functional category of the animal.10, 25, 26 Specifically, most people express much less moral concern for farmed animals such as pigs and chickens and for certain unappealing or dangerous wild animals such snakes and frogs, than for companion animals such as dogs and cats and for appealing or cute wild animals such as dolphins and chimps. The findings concerning farmed animals in particular show that for people who eat animals, perceiving an animal as a ‘food animal’ matters significantly in shaping their judgements about the moral status of animals. If this is indeed correct, the moral divide between different types of animals should be clearly weaker or non-existent for vegans. But what about vegetarians? Do vegetarians and vegans differ from each other in their moral concern for animals? The answer is yes.

As part of our survey, we presented participants with a list of animals belonging to different categories and asked them to rate how much moral concern they feel compelled to show each animal. As expected, and presented in Figure 3, vegan participants consistently expressed a very strong moral concern for all animals without discriminating between farmed animals, appealing wild animals, and companion animals. They only showed a slight drop in moral concern for unappealing wild animals. Conversely, among vegetarian participants we found clear evidence for a perceived moral divide between animals, similar to the moral divide observed among omnivores in previous studies. Specifically, vegetarians felt more morally obliged to show concern for companion animals than for any other animal category and felt clearly less morally obliged to show concern for farmed animals and unappealing wild animals.

Figure 3

Conclusion and Implications

We will now return to the main question: what motivates people to go vegan? The available evidence suggests that by and large the vast majority of people who go vegan do so predominantly for the animals. This is reflected in the findings of our study, which revealed some key moral psychological differences between vegetarian and vegan participants. Specifically, although both groups seem to have similar moral motives to abstain from meat consumption, only vegans apply these same ethical values consistently to a wider range of animal-based products. Vegetarian and vegan participants also differed in their perceptions of the moral status of different types of animals, especially with respect to unappealing wild animals and farmed animals. In other words, a stronger and more consistent endorsement of anti-speciesist principles distinguished vegans from vegetarians.

Increased moral concern for animals and opposition to harming animals thus seems to constitute necessary (but not sufficient) psychological factors that need to be present before people decide to go vegan. Health and environmental motives tend to play a less central role given that both vegetarians and vegans did not differ greatly from each other in the perceived importance of these motives. Therefore, it could be argued that animal ethics deserve to be at the heart of vegan advocacy campaigns while health and environmental benefits should receive proportionally less attention. Before jumping to conclusions, however, more research is needed to replicate the current findings in more diverse and representative samples of vegans and vegetarians.

The findings also raise a question; why is it that vegetarians do not apply their moral principles to other animal products and turn vegan? One possible explanation might be that they fail to acknowledge the animal suffering associated with dairy and egg production and therefore consider it less relevant as a motive to reduce or ditch dairy and eggs. A greater focus on the harm being done to animals in the dairy and egg industries, combined with a consistent rejection of exploiting animals for human benefits may help tackling this issue. However, and speculatively, just like meat eaters often wilfully ignore or deny the suffering of animals slaughtered for meat, cheese and cake eaters may wilfully ignore or deny the suffering of animals in the dairy and egg industry. Clearly, there is a need for more research into the psychological strategies and justifications used by vegetarians that make consuming dairy and egg products appear morally acceptable.

Table 2.

|

Motives not to eat meat

|

Motives to eat vegan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. Health (H), environmental (E), and animal ethics (A) motives. Participants rated the importance of each reason on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all important) to 7 (Extremely important). Items were based on the validated Vegetarian Eating Motives Inventory developed by Hopwood et al. (2020). |

|

The views expressed by our Research News contributors are not necessarily the views of The Vegan Society.

References

- Fox N, & Ward K. Health, ethics and environment: A qualitative study of vegetarian motivations. Appetite 2008; 50(2–3), 422–9.

- Hopwood CJ, Bleidorn W, Schwaba T, & Chen S. Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(4): e0230609.

- Ruby M. Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite 2012; 58(1), 141e150.

- Rosenfeld D & Burrow A. Vegetarian on purpose: Understanding the motivations of plant-based dieters. Appetite 2017; 116, 456–63.

- Rosenfeld, D. The psychology of vegetarianism: Recent advances and future directions. Appetite 2018; 131, 125–138.

- Hodson, G., Dhont, K., & Earle, M. Devaluing animals, “animalistic” humans, and people who protect animals. In Dhont K. & Hodson G. (eds.) Why we love and exploit animals: Bridging insights from academia and advocacy. Routledge; 2019.

- MacInnis C. & Hodson G. It ain’t easy eating greens: Evidence of bias toward vegetarians and vegans from both source and target. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2015; 20(6), 721–744.

- Pfeiler T. & Egloff B. Examining the "Veggie" personality: Results from a representative German sample. Appetite 2018; 120, 246–255.

- Dhont K., & Hodson G. Why do right-wing adherents engage in more animal exploitation and meat consumption? Personality and Individual Differences 2014; 64, 12–17.

- Dhont K., Hodson G., & Leite A. Common ideological roots of speciesism and generalized ethnic prejudice: The social dominance human-animal relations model (SD-HARM). European Journal of Personality 2016; 30(6), 507–522.

- Dhont K., Hodson G., Leite, A., & Salmen, A. The psychology of speciesism. In Dhont K. & Hodson G. (eds.) Why we love and exploit animals: Bridging insights from academia and advocacy. Routledge; 2019.

- Caviola L., Everett J., & Faber N. The moral standing of animals: Towards a psychology of speciesism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2019; 116(6), 1011–1029.

- Hodson G. & Earle M. Conservatism predicts lapses from vegetarian/vegan diets to meat consumption (through lower social justice concerns and social support). Appetite 2018; 120, 75–81.

- Judge M. & Wilson M. A dual-process motivational model of attitudes toward vegetarians and vegans. European Journal of Social Psychology 2018; 49, 169–178.

- Stanley, S. Ideological bases of attitudes towards meat abstention: Vegetarianism as a threat to the cultural and economic status quo. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2021.

- Rothgerber H. Attitudes toward meat and plants in vegetarians. In Mariotti F. (ed.), Vegetarian and plant-based diets in health and disease prevention. Academic Press; 2017.

- De Backer C.J.S. & Hudders L. From meatless mondays to meatless sundays: Motivations for meat reduction among vegetarians and semi-vegetarians who mildly or significantly reduce their meat intake. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 2014; 53(6), 639–657.

- De Backer C. & Hudders L. Meat morals: relationship between meat consumption consumer attitudes towards human and animal welfare and moral behavior. Meat Science 2015; 99, 68–74.

- Rosenfeld D. Why some choose the vegetarian option: Are all ethical motivations the same? Motivation & Emotion 2019; 43, 400–411.

- Bilewicz M., Imhoff R., & Drogosz M. The humanity of what we eat: Conceptions of human uniqueness among vegetarians and omnivores. European Journal of Social Psychology 2011; 41(2), 201–209.

- Rothgerber H. A meaty matter. Pet diet and the vegetarian’s dilemma. Appetite 2013; 68, 76e82.

- Rothgerber H. A comparison of attitudes toward meat and animals among strict and semi-vegetarians. Appetite 2014; 72, 98–105.

- Rothgerber H. Underlying differences between conscientious omnivores and vegetarians in the evaluation of meat and animals. Appetite 2015; 87, 251–258.

- Dhont K. & Ioannidou M. The moral psychological differences between vegetarians and vegans 2021 (manuscript in preparation)

- Krings V., Dhont K., & Salmen A. The moral divide between high- and low-status animals: The role of human supremacy beliefs. Anthrozoos; 2021.

- Leite A., Dhont K., & Hodson G. Longitudinal effects of human supremacy beliefs and vegetarian threat on moral exclusion (vs. inclusion) of animals. European Journal of Social Psychology 2019; 49, 179–189.