In this balanced thought piece, Researcher Network member, Imogen Allen, considers if veganism is a way forward from coronavirus.

SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes Covid-19, is believed to have originated from a “wet market” in Wuhan, China. At these markets, a wide range of exotic and farmed animals are crammed into cages and sold for food and traditional medicines. The reason it is called a “wet” market is because animals are often killed on site to ensure freshness. Such markets are a hotbed for new and dangerous infections because of the proximity between human and non-human animals; alive, dead and dying.

Exactly how SARS-CoV-2 came to be the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans is debated. A popular theory is that the wet market provided the perfect conditions for a virus to jump from a Rhinolophus affinis bat, to a pangolin, and then to a human, mutating along the way.

Diseases that can be transmitted from other animals to humans, by either contact with the animals or through vectors that carry zoonotic pathogens to and from other animals to humans, are defined as “zoonotic diseases” or “zoonoses.” In general, each coronavirus causes disease in only one animal species, so they are not technically “zoonotic”, nevertheless, because the new mutated version of the virus used an animal host as an intermediary, public health experts have been referring to it as such.

Covid-19 is far from the only zoonotic killer to have emerged in recent years. Approximately 60% of all human diseases and around 75% of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic.

Looking at the origins of a number of zoonotic pandemics and epidemics, vegan activist “Earthling Ed” recently observed that "the one thing they all have in common is that they started because of our exploitation of #animals" and that “COVID-19 would not exist if the world was vegan."

The post has sparked a degree of debate. Fact checkers at USA Today, although implicitly finding much of the claim to be true, declared it “partly false”, suggesting that while “many infectious diseases that have wreaked havoc on humans have come from animals, it is not entirely the case that ending the consumption of animals would put an end to such diseases.”

Recent epidemics and pandemics

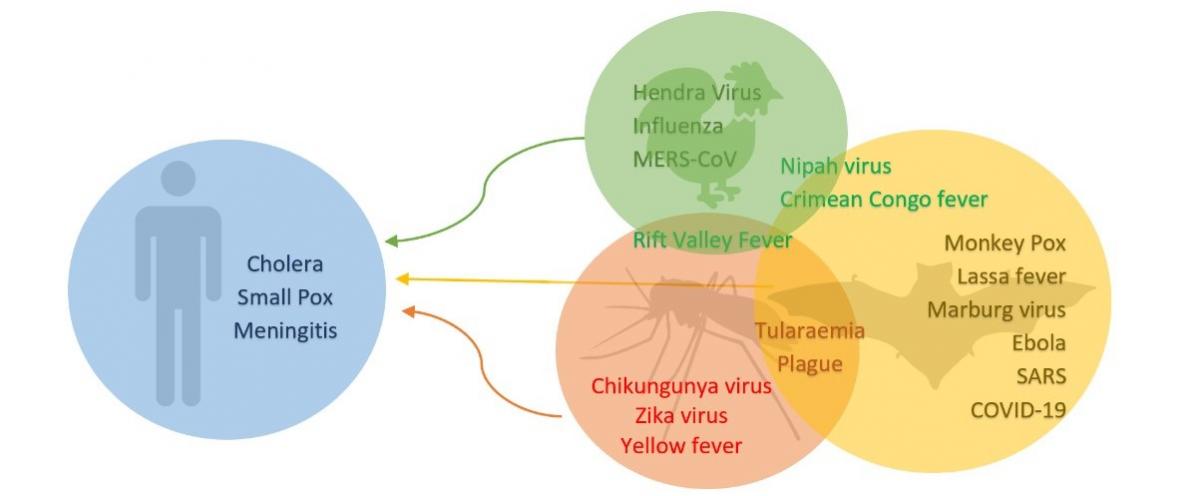

Given the circumstances, a reasonable starting point seems to be the diseases listed as “epidemics” and “pandemics” by the WHO. As shown in the green and yellow circles below, the majority (14/20) of the diseases within this section are zoonotic in origin.

Figure 1: The 20 diseases currently being watched under the epidemic and pandemic section of the WHO website. Blue circle – diseases transmissible by humans only, green circle – zoonotic diseases where farmed animals and domesticated animals are the reservoirs, yellow circle – zoonotic disease where wild animals such as bats, rats and civet cats are the reservoirs, red circle – vector borne diseases where vectors such as fleas and mosquitos are the reservoirs. (Figure created by author.)

The roots of these zoonotic diseases are likely to lie in the close proximity we have with other animal populations. As a recent BBC article points out, all animals carry pathogens and their evolutionary survival depends on infecting new hosts and different species. Therefore, living in close proximity means there are more opportunities for this to happen, hence USA Today’s conclusion that it is not veganism per se, but limiting contact with other animals generally, that would be necessary to lessen the chances that viruses and other pathogens transfer between species and infect humans.

Whilst it is hard to fault USA Today on the technicalities of this, it seems to lend itself more to a conclusion that Earthling Ed’s statement was largely true, rather than “partly false”. Indeed, four of the diseases (namely, Hendra virus, Influenza and MERS-Cov as well as Rift Valley Fever) are linked directly to farmed animals and animal used for labour. In a world without non-human animal exploitation, we never would have brought billions of these animals into existence, so human-non-human animal contact would necessarily be more limited. These diseases would likely never have emerged, let alone spread to humans.

Not all zoonoses, however, come from domesticated animals. A large proportion are linked to wild animals including small mammals such as bats and rats. Admittedly, a global transition to vegan diets would not have the same effect on these wild populations as it would on the farmed animal populations that cause the zoonotic diseases above (Hendra virus, Influenza, MERS-Cov and Rift Valley Fever). Nevertheless, it is wildlife trade and the practice of eating bushmeat that has been responsible for putting wildlife in the conditions where diseases such as Ebola, SARS and Covid-19 are able to infect humans. Wet markets in particular are a double threat: they bring together many different animal species and place a great deal of stress on immune systems, thus creating the perfect environment for viruses to take advantage. Consigning meat and animal exploitation, including wet markets, to history would significantly limit the potential for such outbreaks.

This vegan world would not, however, be a total defence against zoonoses. There is evidence that urbanisation, increased deforestation and the encroachment of cities into wildlife spaces could continue to create problematic pathogen pathways by facilitating the human–wildlife interactions necessary to kick-start contagion.

Historical zoonotic pandemics

Covid-19 is by no means the deadliest zoonotic pandemic in history. At the time of writing (1st April) Worldometer estimated 44,208 people had died so far from this novel virus. In comparison, the 1918 influenza pandemic (avian origin) is estimated to have killed 50 million people worldwide, which was 2.7% of the world population. Additionally, the H1N1 virus (swine flu) killed 151,700–575,400 people worldwide in the first year of circulating.

Other leading causes of death

Not all communicable killers reach “epidemic” or “pandemic” status. Oxford University’s “Our World in Data” provides a list of the leading causes of death worldwide in 2017, containing a number of other communicable diseases (lower respiratory infections, diarrhoeal diseases, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, malaria and meningitis), some of which are linked to or exacerbated by our exploitation of animals.

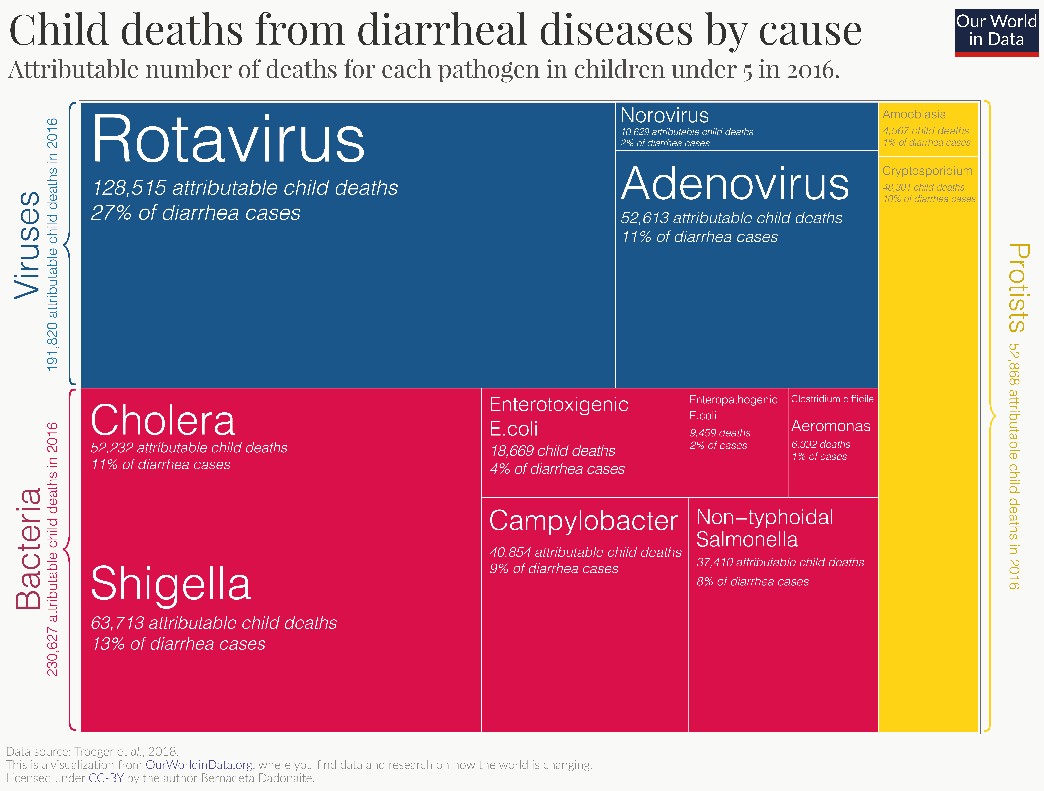

Diarrhoeal disease caused 1.6 million deaths in 2017, one third of whom were children under five years old in developing countries. Focussing specifically on child deaths, Figure 2 shows the percentage of diarrhoeal disease cases caused by different types of pathogen. Whilst the majority of these pathogens are non-zoonotic, Cryptosporidium, Campylobacter, Salmonella (non-typhoidal) and E. coli are, and accounted for a large percentage (33%) of deaths. It is also important to note that aside from being a lead cause of child mortality, they are responsible for a significant amount of discomfort and economic loss globally. An estimated 600 million people are victims of food poisoning each year, with many cases being linked to the bacteria in Table 1. Again, a vegan world would significantly reduce the suffering and death caused by these diseases.

Figure 2: The percentage of diarrhoeal disease cases caused by different types of pathogen.Data source: Troeger et al., 2018. This is a visual taken from OurWorldinData.org. Licensed under CC: By the author Bernadeta Dadonaite.

Table 1: Animal reservoirs of Cryptosporidium, Campylobacter, Salmonella (non-typhoidal) and Escherichia coli.

|

Bacteria |

Animal sources |

|

Cryptosporidium |

Wildlife, farmed animals, cats and dogs[1] |

|

Campylobacter |

Poultry, cows, pigs, sheep, ostriches, cats and dogs[2] |

|

Salmonella (non-typhoidal) |

Poultry, pigs, cows, cats, dogs, birds and reptiles [3] |

|

Escherichia coli |

Except for diarrhoeal disease and a small number of cases of tuberculosis, most of the leading communicable diseases that kill are not classified as zoonotic. Nevertheless, there is evidence of adenoviruses crossing host species barriers between humans and non-human primate, bat, feline, swine, canine, ovine, and caprine species. In a vegan world, certain swine, ovine and caprine varieties may never have infected humans in the first place. Similarly with rotaviruses, it is possible that they arose in the human population through zoonotic transmission, and some infection may have occurred through farmed animal excrement within farming communities, and potentially to visitors to the countryside.

A similar argument is true for HIV/AIDS: it is not considered a zoonotic disease, as transmission is limited to between humans only; however, there is proof that “humans are not the natural hosts of either HIV-1 or HIV-2”. A review by Pan et al 2000 states that these viruses have entered the human population as a result of zoonotic, or cross-species, transmission, with the main reservoirs being non-human primates (sooty mangabeys and chimpanzees). Exactly how the transmission occurred is debatable. Pan puts forward two hypotheses: biting, which could equally have occurred in a vegan world, or direct exposure to blood as a result of hunting, butchering or other activities, which most likely would not. In either scenario, leaving wild animals alone is safer, and vegans generally have less cause to interfere with them.

Farmed animal consumption and antibiotic resistance

Looking forward, the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is one of the biggest threats to global health, food security and development today. Many communicable diseases, including pneumonia, tuberculosis, blood poisoning, gonorrhoea and foodborne diseases, are becoming harder, and sometimes impossible, to treat. The WHO states that “the rate at which bacterial strains are developing resistance outpaces the rate at which scientists are developing new medicines that can kill strains”.

Antibiotic resistance, again, is a phenomenon that has been linked to farmed animal consumption. Whilst misuse in healthcare settings is partially responsible, the usage of antibiotics to treat or promote the growth of farmed animals is a major culprit. Unfortunately, owing to lack of regulation, data is unclear. Nevertheless, experts estimate that “global consumption of antimicrobials in animals is twice that of humans”, and usage is expected to increase by 67% by 2030. This is because the demand for animal products is increasing, and, consequently, the number of large-scale farming systems where antimicrobials are routinely used. A vegan world would totally remove the need for the large-scale use of antibiotics in this way.

Of course, organic and free-range farming may also guard against antibiotic resistance to some extent. For example, in poultry systems, there is evidence that “lower stocking densities are linked to lower disease incidence, as air quality is better, wet litter is less of a problem and disease spread is reduced”. Similar results are reported for less intensive beef farming systems. Nevertheless, even in countries like the UK, where the use of antibiotics for farmed and companion animals is strictly curtailed and limited only to veterinary intervention, these animals still account for 36% of antibiotic use. Whilst this may seem like a reasonably small volume when the comparative populations of humans and animals are considered, it nevertheless accounts for a significant proportion of antibiotic use, one which would be negligible in a vegan world.

Plant-based pathogens?

Transitioning to a plant-based diet would mean a drastic change in the types of food most people are consuming. As we swap meat for plants, could we swap zoonoses for plant-based pathogens?

In short, probably not, or atleast not on this scale. There is evidence of fungi producing mycotoxins, such as those found in maize, pistachios and peanuts, presenting a public health problem. However, in general it’s rare for plant pathogens to cause disease directly in humans.

The threat of plant-based pathogens in a vegan world would probably lie not in humans catching them from plants, but in them annihilating our food. Reduced crop yields caused by plant disease are a well-known and pressing issue threatening global food security and human health. Scientists have predicted that pests and plant diseases are responsible for reducing the yields of crops that make up half of the global food supply (wheat, soybean, potato, maize, rice) by 10–40%. Therefore, plant pathogens may create an indirect risk to human health by causing undernutrition, which is known to render humans susceptible to infection and even death.

The question, therefore, is whether an exclusively plant-based diet would be too risky. Currently, a substantial quantity of crops are actually fed to farmed animals. Therefore, removing the middleman, if done correctly, could lead to a greater abundance of food, particularly in the most developed countries.

The problem would be one of distribution: some terrains are hostile to plant-based agriculture, so grazing animals, hunting and fishing remain a vital source of food. Animal farming, wildlife trade and pets are also a major source of income and support the livelihoods of many, particularly poverty-stricken individuals in developing countries. It is estimated that “nearly 1 billion people living on less than two dollars a day are dependent to some extent on livestock”. Most of these individuals are found in South Asia (predominantly India) and sub-Saharan Africa.

Therefore, an immediate ban on animal farming and the consumption of animals for food would lead to severe consequences. Poverty levels in already vulnerable areas would be greater, which would inevitably lead to starvation and undernutrition. These may not be communicable diseases, but large human populations with weakened immune systems would create ideal conditions for them to spread.

The case for gradual transition

It is impossible to predict what the risk of infectious disease would be if the world were to become predominantly vegan overnight, and it would be impractical to do so. Nevertheless, for those societies capable of doing so without creating food shortages or poverty, steadily reducing animal farming in favour of plant-based alternatives should, in theory, reduce the risk of a number of lethal communicable diseases.

The views expressed by our Research News contributors are not necessarily the views of The Vegan Society.